An exciting new technology is known as “percutaneous” or “trans-catheter” valve replacement.

Currently, the TAVR procedure is used for aortic stenosis, which means that the patient’s aortic valve is restricted from opening, typically due to the development of calcium deposits on the valve. Believe it or not, this technology allows doctors to place a new valve in your heart without your having to undergo open heart surgery. In the TAVR procedure, we do not open the chest and we do not use the heart-lung machine. We don’t stop the heart. We’re able to do about 90% of them just from catheters in the groin, like a cardiac catheterization procedure. Using x-ray guidance, we can place a new valve inside the patient’s own valve, pushing aside the calcium deposits with a stent. Most patients can go home in just a day or two after a TAVR procedure.

The procedure was approved in November 2011 by the FDA in the United States. In order to have a TAVR, you need to be either high risk or what they call intermediate risk patients. I was among the first in the country to do the TAVR procedure in 2012, and I was a principal investigator for what is known as the low-risk TAVR trial. We anticipate this spring or summer that the FDA will approve this technology for patients who are low risk.

First Trans-Catheter Aortic Valve (TAVR) Procedures Performed in Region at Lehigh Valley Health Network

Lehigh Valley Health Network performed the first

There were a lot of people behind the scenes who made the launch of our trans-catheter program so successful. Our dedicated operating room and cardiac catheterization nurses, anesthesia, perfusion, and radiology colleagues worked so hard to

Here is a picture of our collaborative clinical team standing outside of our hybrid operating room after both procedures were successfully completed and both patients were deemed stable.

Dr. David Cox (Interventional Cardiology); Dr. Patrick Kleaveland (Interventional Cardiology); Dr. Raymond Singer (Cardiac Surgery); Dr. Wilson Szeto (Cardiac Surgeon from Penn); Dr. Bill Combs (Interventional Cardiology); Dr. Gary Szydlowski (Cardiac Surgery); Dr. Matt Martinez (Diagnostic Cardiology); and Mr. Richard Steigerwalt (Clinical Expert, Edwards Lifesciences).

Here is a bedside interview with our first patient less than 2 hours after the surgery!

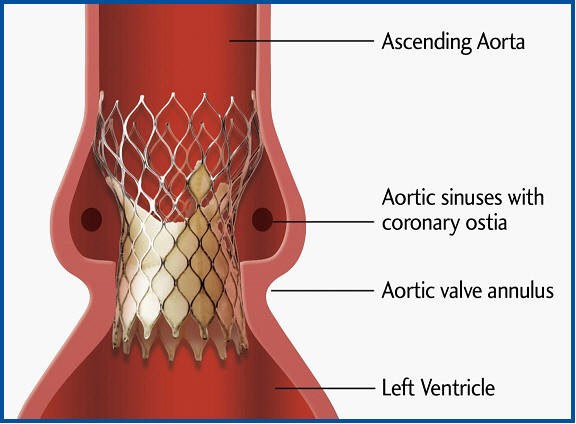

Below is the Edwards Lifesciences SAPIEN percutaneous valve. This is the first trans-catheter valve that has been approved in the U.S. It consists of a bovine pericardial valve that is held together by a collapsible stainless steel frame. At this point in time, almost all of the percutaneous valve procedures are done for aortic stenosis –blockage of the aortic valve.

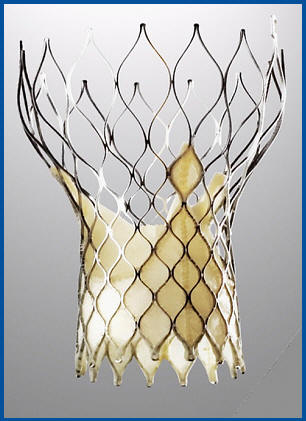

Another percutaneous aortic valve that is under investigation trials in the U.S. is the Medtronic CoreValve shown below.

It also consists of a bovine pericardial valve but it’s held together by a self-expanding nitinol stent. Like the Edwards SAPIEN valve, the Medtronic CoreValve has been used in Europe and is likely to be approved for use in the United States in the next few years.

So, how do they put an aortic valve in your heart without surgery?

So far, there are two approaches: “trans-femoral” and “trans-apical.”

Trans-Femoral Aortic Valve Approach

In the trans-femoral approach, a catheter in placed in an artery in the groin, similar to a standard cardiac catheterization. The difference is that currently the catheter sizes are quite large, so an incision is sometimes required to place these catheters. In time it is likely that the catheter sizes will decrease and will be done “percutaneously” –meaning, by inserting the catheter into the artery without an incision.

The first step is to take a balloon and bust open the aortic valve. After that, the percutaneous valve is put in place and a second balloon expands the new valve, cementing it into position.

Below is an animation of the procedure provided by Edwards Lifesciences.

Trans-Femoral Case Presentation

Below is a patient who was deemed too high risk for conventional aortic valve replacement.

You’re watching the fluoroscopy (moving x-ray) of the valve being opened in place by the balloon. The valve and balloon are inserted via the artery in the groin and followed on the x-ray until it lays perfectly across the old valve.

You might ask, “What happens to the old valve?” Well, that’s a great question. It’s simply gets pushed out the way with the new valve taking its place.

That’s actually one of the controversies about this procedure. Is this “valve inside a valve” technique as safe or as durable as the conventional techniques of replacing a valve… see my discussion below.

Trans-Apical Aortic Valve Approach

Sometimes the femoral (groin) vessels are too diseased to allow for catheters to be placed. In addition, many older patients have a lot of calcified plaques all along the aorta leading back to the heart.

The trans-apical approach alleviates the worry of injuring the leg vessels. By making a small incision in the left chest –the same incision we make for “minimally invasive heart surgery”– the surgeon can place the percutaneous valve directly through the apex of the heart, as shown in the video below…

This so-called “antegrade” approach is a great option in patients with severe peripheral vascular disease, meaning hardening of the arteries leading down to the legs. This approach has been highly successful in Europe with placement times consistently be completed in less than 45 minutes! There are also some reports that the stroke rate may be less with the trans-apical approach.

Trans-Apical Case Presentation

This patient has a completely calcified aorta making both the convention open heart surgery and the femoral trans-catheter approach inoperable.

You can see the catheter entering the heart from right to left across the apex with the catheter remaining perfectly still across the aortic valve.

In the femoral approach, the valve and balloon are on a long flexible catheter which makes it harder to maneuver. In the trans-apical approach, the catheters can be more firm and thus more stable with regards to quick and perfect positioning.

It may seem risky to put a hole in the apex of the heart and to suture it closed, but actually it’s a very old technique that goes back almost to the beginning of heart surgery. Heart surgeons are used to placing sutures and catheters in the heart, of course.

Trans-Catheter Valves and the Hybrid Approach to Heart Surgery

One of the issues with any new, less invasive technology is trying to determine who will perform the procedure.

For example, heart surgeons were trained to perform

The answer is complex and quite frankly, the future is unknown. However, for now, the philosophy is that these procedures should be done by both the surgeon and the interventional cardiologist working together as a team –the so-called “hybrid” team approach.

And, to that point, across the globe hospitals are actually building what are known as “hybrid operating rooms.” The word “hybrid” means creating something that is made of two elements. Therefore, a hybrid operating room combines the radiographic (x-ray) equipment of a cardiac catheterization laboratory with the size, equipment, sterility, and safety of an operating room. These are oversized operating rooms that are equipped with both surgical and x-ray equipment.

The Hybrid Operating Room

Lehigh Valley Health Network has completed the first hybrid operating room in the Lehigh Valley and one of the largest and most advanced in the country.

Not all hospitals will be able to place trans-catheter valves. Only hospitals that perform a high volume of heart surgery, and specifically, a high volume of heart valve surgery will be selected. In addition, the hospital must have quality outcomes and of course, a hybrid operating room. Many experts speculate that fewer than 300 hospitals in the country will be able to perform this procedure.

Lehigh Valley Health Network has one of the largest heart surgery programs in the state of Pennsylvania. And, according to the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council’s report (PHC4), LVHN has some of the best surgical outcomes year after year!

Below are the PHC4 outcomes than were published in June 2011. Most programs receive a “same as expected” result when it comes to mortality. You can see

In addition, only heart programs that have collaborative teams of experienced interventional cardiologists and heart surgeons will be allowed to be trained in the procedure. We developed a collaborative trans-catheter aortic valve team consisting of diagnostic and interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, led by our nurse coordinator, Mrs. Ronnie Moore.

The interventional cardiologists include Dr. Patrick Kleaveland and Dr. David Cox from the Lehigh Valley Heart Specialists, Dr. William Combs from The Heart Care Group, as well two cardiac surgeons, Dr. Gary Szydlowski and me from the Lehigh Valley Heart and Lung Surgeons.

Will percutaneous valves replace open heart surgery?

It would seem unlikely at this point. Keep in mind that coronary artery stenting has not eliminated the need for coronary artery bypass surgery and I suspect there will be a similar balance with these so-called percutaneous valves. Currently in Europe approximately 25% of all aortic valve replacements are being performed using the trans-catheter approach. It is very possible that 50% or more of all aortic valve surgeries may be performed this way in only the next 5-10 years. Nevertheless, there will still be a large number of patients who will benefit most from conventional open heart valve surgery.

For now, in the U.S., these procedures are only being done in the most high risk of patients –that is, patients who are deemed too high risk for conventional techniques. In fact, in order to receive this procedure in the U.S., a heart surgeon actually needs to deem you “inoperable,” meaning that you need to be turned down first for the conventional approach. No doubt as this technology continues to improve, the indications for the trans-catheter procedure is going to expand and likely it will be offered to more and more patients.

Keep in mind, this procedure has its own set of risks.

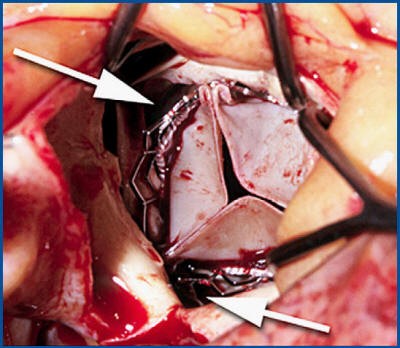

For example, we already know that many patients who received a percutaneous, trans-catheter aortic valve are left with what is known as a “para-valvular leak” or a leaking of blood around the new prosthetic valve as shown below:

This most likely occurs because the original bad valve, full of calcium and debris is left behind, as the new valve is simply placed within the old valve. This can lead to long term instability of the valve or possibly the risk of infection to the new valve, known as prosthetic endocarditis. It could take 10 or more years from now to know the true results.

Another risk of the trans-catheter valve replacement is stroke. In fact, the risk of stroke with this procedure is actually higher than with conventional open surgery. Again, this is likely due to the fact that all of the calcium on the valve is left behind. When the balloon is inflated in order to bust open the old valve, calcium deposits may come loose and go to the head vessels, causing a stroke. Also, the catheters that are used can injure the aorta and the leg vessels causing stroke or loss of a limb. That’s why at this point in time, the procedure is only being performed on the highest risk patients who truly cannot undergo conventional open heart surgery.

And, as I said above, it also means that the safest and most reliable procedure for aortic valve replacement for most otherwise healthy patients remains the conventional open heart surgery procedure.

Preparing for the future…

Below is a talk that I gave to the Board of Associates at Lehigh Valley Health Network. This talk gives the history of aortic valve surgery and nicely illustrates the differences between conventional heart valve surgery and the trans-catheter approach.

Further Reading: